Prophetic Stories or Spells of Destiny?

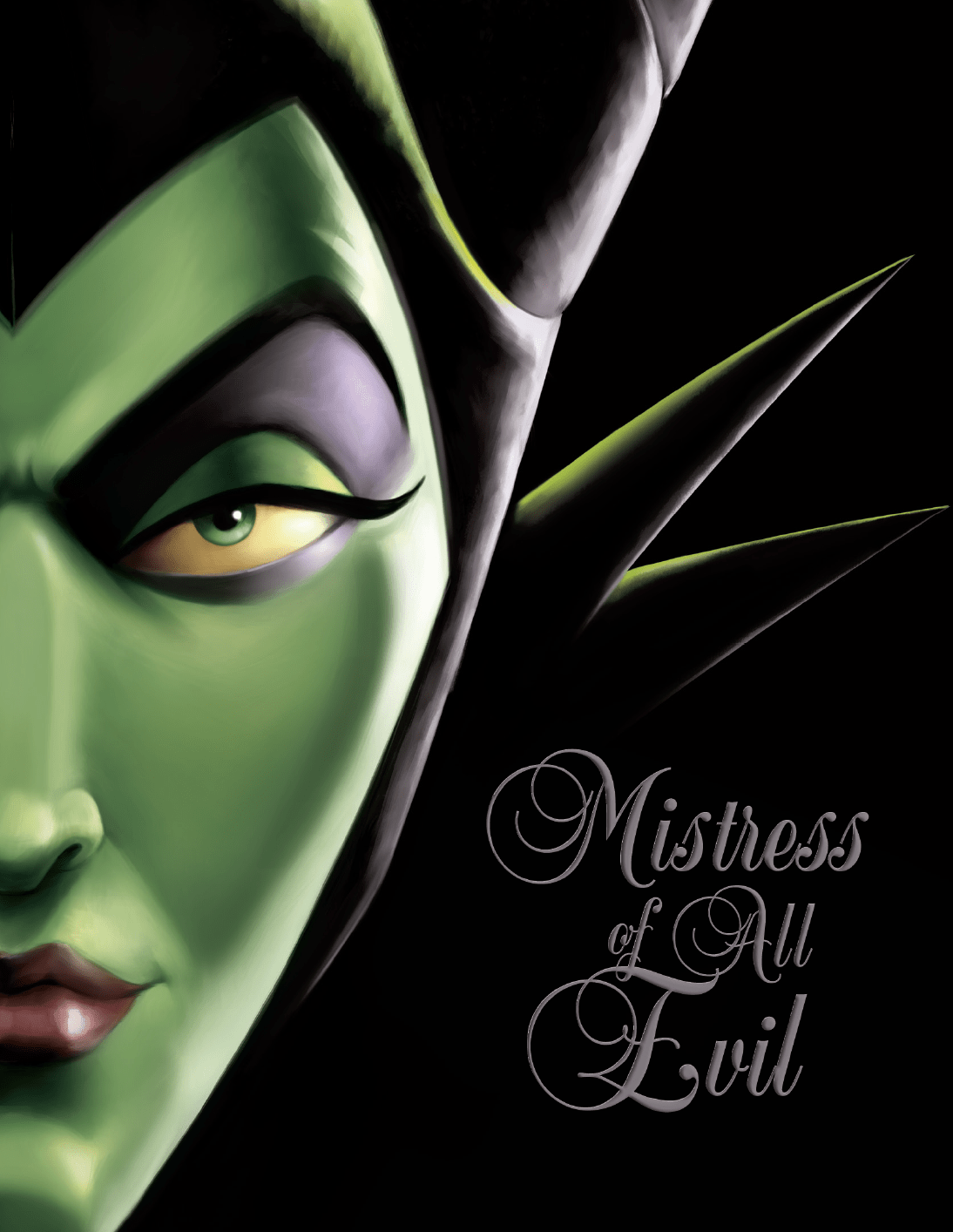

A review of Mistress of All Evil: A Tale of the Dark Fairy by Serena Valentino (Disney Press, 2017)

By Derek Newman-Stille

With Mistress of All Evil: A Tale of the Dark Fairy, Serena Valentino once again adds moral complexity to a Disney villain, providing a backstory that allows the reader to see how her choices were made. Mistress of All Evil examines one of my favourite Disney villains, Maleficent, the villain from Sleeping Beauty. Rather than turning Maleficent into a hero as the film Maleficent did, Valentino makes her a villain with a complicated morality and provides more context for why Maleficent feels justified in her actions.

Valentino’s Maleficent is a character whose life has been shaped by loneliness, isolation, and rejection… and along with all of that, a fuse that, once lit, causes her to lose control. Although this Maleficent was born in the fairy realm, she was born from a tree covered in ravens and rather than having wings, she was born with horns. She was rejected by the fairy community and teased for her difference. Even the Fairy Godmother from Cinderella and the three “good fairies” from Sleeping Beauty have sought to reject and isolate her from the rest of fairy kind. Maleficent buries herself in books and accepts her isolation until she discovers Nanny, a figure that has appeared in all of the other Valentino Disney books. Nanny gives Maleficent a sense of belonging and a sense of family, but like most things in Maleficent’s life, this sense of comfort is short lasting and she loses her connection to Nanny for many years as Nanny loses her memory and Maleficent thinks she is dead.

Valentino constructs a meta narrative about storytelling, linking tales to ideas of fate and toying with the idea that Maleficent’s story has already been written. Snow White discovers a fairy tale book that already has Maleficent and Aurora’s tale written down and characters start to wonder whether the book is a prophetic book or whether it is a spell, locking characters into a narrative that was written to control them.

Like most of Valentino’s book, every character thinks that they are doing the right thing, believing that they are making things better for others and protecting others from terrible truths, but, of course, secrets and lies are dangerous in fairy tales and they always have consequences.

Mistress of All Evil: A Tale of the Dark Fairy, although written for young adults, is a complex exploration of fairy tales and ideas of tradition, challenging ideas of the simple Disney narrative and the easy morality of fairy tales for children and providing an engagement with ideas of “best intentions” to explore how even people who think that they are doing the right thing can end up harming others.

To discover more about Serena Valentino, visit http://www.serenavalentino.com

To find out more about Mistress of All Evil: A Tale of the Dark Fairy, visit http://books.disney.com/book/mistress-of-all-evil/