Unjust Desserts

By Derek Newman-Stille

I was never particularly gifted in anything. I found most of my life in the village a struggle just to get through each day. I couldn’t relate to any of the townsfolk, couldn’t get particularly excited or interested in the tending of fields, the husbandry of sheep, or the petty gossip about which town member was the most disliked and therefore inherently suspect this week.

I didn’t participate in the gossip because I seemed to be the only one who made the connection between gossip and the arrival of the Witch Hammers, who seemed to take away the problematic, least liked person during each of their visits. I seemed to also be the only one who recognised that these rumours tended to start whenever someone had something that others wanted. I recognised early on that I had a curse. It was called “empathy” and it haunted me like a repeated visit from the dead. And I lacked the thing that the town obviously thought was the most important: “greed”.

Thankfully I had my own gift. I called it “glucomancy”, the power over sweets – to shape them to my will and desire. It took a lot out of me, but it was worth it to see the magic in people’s eyes when they came into my cake shop and ate one of my sweets for the first time.

But as I got more and more involved in the creation of wonderful desserts, I forgot what this town had taught me… that desire is dangerous, that want got people hurt. I was reminded the first time I showed someone my gift to shape the sweet, to make honey flow from the air and become flavour gold.

There was something particularly magical about the reactions of children when they saw a new dessert, so I tried, as much as possible to always vary my results, to shape desserts to match their passions and loves: creating a cake shaped like a sleeping kitten for Sally, the little girl who adopted a barn cat with a broken leg; shaping a lollypop tree for Jim, the little boy who wanted to grow up to be a lumberjack; creating an apple pie covered in the glittering diamonds of sugar crystals for Janette, the little girl whose mother remarried to the local orchardman…. My desserts were offerings to those faces full of wonder and the reward was seeing their eyes sparkle with want when they saw their treat appear before them. Each creation was a mosaic of sweet lives.

I suppose it was my belief in the essential innocence of children that caused me to eventually show the secret of my magic. I was just closing up shop for the day when two sets of shining eyes appeared at my window. I never learned the name of the boy and the girl even though later I learned the name of their father. They told me that they were the children of labourers – that their parents worked the fields for the local nobleman, Duke Richmond, and that they had heard that I would give treats to the poor children of the village.

Because I was closing shop, I hadn’t had a chance to work my particular kind of glucomancy for the day. I generally liked to create treats anew each day, so the end of the day was sort of a rest period for my power… but I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to bring a sense of joy to their round little faces, especially if they hadn’t had the resources to try my desserts before. So, i decided to reveal my glucomantic secret, to perform the art of sweetcrafting in front of a crowd… or at least in front of these two little innocents.

“I will make treats for you, but i need you to keep the way I make them secret.”

“Why?” The boy asked, his little face scrunched up with curiosity.

“Not everyone is happy with people who are different… And the way I make my sweets is… different.”

“Why?”

“Let me… let me show you.” My heart began beating wildly, fear and excitement blended.

I raised my fingertips to the sky, feeling golden mist gather around them, honeyed dew drops touching the ends of my fingers. I pushed a little more of that something through the tips of my fingers as my heartbeat increased. Blood pulsed to my fingertips, stinging the ends of my fingers like nettle as dew became sweetness.

I could feel flowers around me pulse in ecstasy, secreting nectar and pollen into the air, letting the wind breathe it up and bring it to my fingers to mix with the sweetness exuded through my blood. Flowers breathed out nectar as fluid light, gathering as drips around my hands. I flicked my wrist, spinning sweet into strings of sticky sweet light, twisting gummy brilliance between my fingers as I wove it into shapes.

I opened my eyes gently, wanting to see that glint of excitement on the faces of the children, that sparkle of magic reflected in their eyes.

Instead I saw only horror. Their faces were frozen between screams, eyes wide, glistening not with excitement but tears. The shuddering that I had been hearing was not amazement, but disgust.

They both waved back and forth on their feet, taking confused steps backward, slowly, knees wobbling under them.

The honey collecting around my fingertips instantly froze into solidity around my hands, trapping them in place.

“Wait… I’m sorry, I -”

The sound of my voice broke the spell of horror around them, allowing them to leave, trailing out the shop door with the smell of urine following them overpowering the scent of honey and nectar. I tried to move to follow them, but the honey had formed panes of sugared glass around my hands, holding them in place.

I pulled my arms back and forth, finally shattering the glass around them, fragmenting it into pieces that bit into my skin, cutting deep into flesh and spouting blood. I couldn’t follow them now. I looked like a murderer with hands slashed in blood, like the nightmare witch of the town’s myth.

Desire and wonder carried that tainted sting of horror and pain.

I gagged.

****

The smell of soot, charred and acrid broke the smell of honey that always seemed to mist in my dreams each night, that weaving of want and need.

I coughed, but each breath sucked in more smoke, a taste of peppers and limes.

I reached to cover my mouth and tasted iron. I spat out that combination of blood and soot.

My eyes shot open to a sky painted with a smoky red hue, as though dawn’s rosy skirt was muddied by her passage. It matched the blood dripping from my torn fingers.

I had made the right decision to leave the town during the night. This is probably the first time I have actually thanked my lack of faith in my town, celebrated my distrust.

I knew I was smelling the burning of my cake shop, smelling my life rendered into smoke. Better my lifehood rather than my body itself. I had still escaped burning by the town that was obviously quick to mobilize to remove the unusual, the other in their midst.

The smell was the scent of purging.

I picked up my bag with my few belongings… mostly clothing, because what else would I want? There’s nothing to connect me to anyone else. My family had rejected me early on, so I had no mementos of them, no need to hold onto memories that were shaped by a persistent sting.

I heard a whispered buzzing sound, distant, almost an undertone to the wind. It always seemed to drift in when I remembered, when I submerged into the forgotten.

When mother slapped me, I knew that it was a manifestation of her own pain, the sting of her hand on my face mirroring the pain within her, as though she needed to share it before it consumed her entirely.

So it became a shared meal, consumed by and consuming two, and I was well-fed as a child.

“You aren’t even mine” she would yell, “You are a plague”, “You are a horror”, “Monstrosity”

These critiques became stronger as I showed how different I was, disconnected from expectations about what a child should be like.

She would stare at me for hours, eyes scanning my face, my eyes, a diagnostic gaze just to see my flaws. “Your eyes are so big… unnatural. Brown like dirt. Your entire face is lost in your giant eyes…. Which I suppose is a good thing. It helps to hide your cheekbones, so high on your face and your yellowish tone, jaundiced,… sickly. You are all bile. You don’t even look like us. I sometimes wonder if you’re even our child or if you belong to Them.”

I had always worried that Mother had been raped, that her rapists were the ‘Them’ she would allude to, the strange Other that had infected her and planted itself inside her womb. But I asked my father about it on his death bed, when I snuck back into my childhood home to see him before he died. He told me then that mother saw me as ill because she herself was ill, but her illness was one of the spirit rather than the body. “She changed, and I am not sure if it is because we made love and she became pregnant at her first sexual experience, or whether she was traumatized by what happened after. I know it is weird to hear about this… about your parents in that situation, but… I don’t know, I just need to tell you so that you know what happened. We made love outside, in the lavender field, and when we… well,… when we finished making love, she rolled over onto a bee. It stung deep, but it wasn’t just regular pain like the rest of us would feel. Her pain was… well, it made her become puffy, have difficulty breathing. It was like the bees sucked the life out of her…. and, well, she thought that it tainted her womb with its sting, that it poisoned her… and through her… that it poisoned you. You were always poison to her…. – no, I don’t mean it like that, I mean that she saw you as poison. You were sweet. You never deserved the sting of her harsh words.”

I was still jaundiced, still ugly in all of the ways she saw me to be. I have tried to cover it with kindness, but that horror still shapes me, and everyone can see it. It is a miracle that I hadn’t been targeted by the Witch Hunters before now.

My history and body have always been inscribed by horror, with the grotesque.

As the buzzing recedes and the blackness at the edges of my vision retreat, I am able to pick up my bag of belongings and throw it over my shoulder. I breathe in until the headache is gone.

Closed petals of flowers begin to stretch their dew soaked velvet out to the awakening sun, tasting the sweetness of the morning air. Like crumbs left on a path, I follow the spots of floral brilliance as I wander toward the woods.

The sweet smell of cedar fills my nostrils, air tacky with sticky sap. My fingers naturally reach out toward the pine needles and cedar leaves, so green I could taste the chlorophyll through my fingertips. The air in the village was full of sweet scents for my magic to draw from (tastes of the harvest), but the air of the forest is pure honey with layers of flavour. I could feel it feeding my glucomantic ability, surging flavour through my bloodstream.

I had become a town girl, accustomed to the presence of people and the clear layout of paths and streets. The forest was a place of meandering mystery and it seemed to wash together in a sea of green, surging with leaves, needles, ferns, grasses, and carrying the occasional dots of colour, flowers opening to pollinate, to call in lovers with kisses carried through the breeze. The forest was a place of uncertainty and in this uncertainty I saw the potential for a life that could float away from village life.

My feet eventually found an orderly path, one that human feet had carved into the forest floor and despite my better judgment, I followed these steps. My desire to be with my own kind warred with my wariness of the cruelty people are capable of. I kept walking in a daze, partially shaped by a day of wandering through wooded obscurity.

The forest opened up into a clearing whose centre was filled with hives in orderly rows, bees made to live like humanity in controlled production centres where they saw no profit of their own. The hives stood on wooden logs, were worked into pottery vessels, wooden boxes, and woven straw baskets, human technology and bee architecture interwoven without the collective power of cooperation it would suggest. This is a parasitic role, with humanity feeding off of the bees and taking the food from their young.

Smoke drifted across a few of the hives, making me freeze in place. The scent of smoke had always unsettled me, but that unsettling was heightened by the burning of my own home and business. I could see shapes moving through the smoke, men with lit sticks billowing smoke, waving it around the hives. Others carried ceramic jars, collecting the honey from the bees who were displaced from their homes. It shaded of lynching and theft – human greed and human violence intertwined.

The buzzing of displaced, smoke-drowsy bees settled around me. I could feel thousands of eyes settling on me, could feel the twitching of antennae tasting my skin, and I could smell sweet nectar on their tiny bee fuzz. The tiny hairs on my own arms lifted slightly at their touch… not out of fear of being stung – that thought hadn’t occurred to me at the time – but rather a strange connectivity, a skin-to-skin conversation that was occurring through their dancing on my skin, raising goosebumps across my flesh as limbs moved in delicate circles.

I could feel myself wavering slightly on my feet, the black spots creeping into my vision with the buzzing.

Wings fluttered and they lightly dusted my hair with pollen, then gently stroked it off of each follicle to taste it again, kneading their hands together in delicate tickles. My skin tingled with thousands of lives touching down and alighting until I smelled of bee.

One of the men with a burning, smoking branch looked with red-rimmed eyes toward the flow of bees that led to me at the edge of the forest.

He coughed several times before managing to get out “Hey, there’s a girl there. What’s she doing.”

“Hey, who are you? What are you doing there?”

I snapped back to alertness, the droning trance fading into harsh human voices.

My feet involuntarily began retreating until I felt the dance of the bees rise up as they started lifting off from me. Where their droning was meditative before, now it seemed to roar. Their gentle dance upon my skin became a war dance, angry feet pounding into my flesh. They spoke my own anger of displacement back to me, the feeling of being homeless, the honey shaped by their hard work collecting nectar, cooling it with their wings in preparation to feed their young taken from those youthful mouths.

My own rage spilled out like nectar from a closed flower, glistening and bright. The honeyed air flowed into sharp points at the tips of my cut and bleeding fingers, spines of crystalline sugar shaped unconsciously by my glucomancy. Each finger became a stinger, barbed at the tip and craving the taste of flesh.

The bees alighted, buzzing a song of violence. The smoke seemed to part at our collective movement, pulled away with the breeze of thousands of wings. Our movement formed an arrow and despite the point of that human and bee arrow flowing toward them, the men could only see a crazy woman, not a threat.

“What the hell is she doing? Is she being attacked by those bees.”

“She’s just crazy. Her hair is full of twigs and she’s covered in mud. The bees won’t be able to sting her through all that shit.”

“At least wave some smoke toward her, chase off a few of those bees. They sound enraged.”

“Do you want to get close to her? Look at her!”

“Fine, give me the branch.”

The man’s breath blew across the burning branch, lighting embers and billowing white smoke. I could see his breath catch as he looked into my eyes. An involuntary breath pulled in acrid smoke and he coughed.

The bees surrounded the men as I shoved the spires of sugar into their skin.

***

I looked down at the sharp tips of glazed honey at my fingers, the translucent amber stained with human gore. I couldn’t look at them without remembering the way human fat felt as it parted with each sting of the sugar-tipped spires, mixing sweet and horrifying.

I am normally someone who knows herself well, who is aware and conscious of her intentions. I suppose that happens when one is made insecure by a society that fears difference. But I couldn’t discern how I felt. No amount of logic or self reflection could tell me how I felt… or how I should feel.

As I looked around at the husks of the bees who had stung the beekeepers, I realised that like them, those yellow and black shells emptied of their bee venom with their stings to die on the ground now that their venom sacks had ripped from their bodies with their barbed stingers… I too was emptied of my own venomous anger, an anger I denied as I fled from the village with only survival in mind…. The passing of the venomous anger didn’t leave relief in my system, but rather a void, a missing space, a strange emptiness. My body didn’t remember what used to be there, what occupied that viral emptiness where every part of me now seemed to try to rush to fill, leaving me awash with uncertainty.

Not all of the bees had died in the attack on the beekeepers, that desperate bid for freedom, and the remaining bees settled on my skin, dancing patterns of mourning for their lost sisters, tasting me to see if I shared their pain and emptiness, their loss. They lapped at the mix of blood and sugar at my fingertips, tasting the sweetness and gore.

I felt myself swaying back and forth. Part of me knew this was probably a form of shock, by body literally rocked with the wreaking sobs that wouldn’t express themselves because they were swallowed by the horrible emptiness of the void within, an echo chamber for my sorrow… But part of me kept convincing itself that it was dancing patterns for the bees, that I mirrored their grief dances with my gangly human body, lacking the precision of their furred, winged movements.

I could feel the grasses and flowers breaking under my stomping feet as I let myself dance, releasing a sharp vegetative scent into the air, wet and dewy with spice to cover up the bitter scent of drying blood.

I picked up the ashy remains of the hives, burned by the beekeepers in their attempts to ward us off. I dropped by clothes to the meadow floor, exposing my body for the bees, not wanting a barrier between skin and fuzz. My fingers were still sharpened tips, made sharper by the bees who licked blood and honey from them. I smeared the ashes from the beehives into stripes on my skin, turning the fire of separation and ashes of the past into markers of community, my belonging with my striped sisters. I stung myself with my spired fingers, tattooing bee patterns into my human flesh, making home in community and a shared language of stripes.

***

I formed the hexagonal panes of sugar into stained glass, bees weaving them together with their own honeycombs of wax and honey. Our communal house was shaped of flavour, weaving the art of the forest into a structure of taste planes, taking on flavours of lavender, strawberries, wild cherries, producing wild scents as the sun shown through the panes of sugared glass.

Although the bees seemed to prefer the symmetry of hexagonal shapes, I added artistic flares to the panes I created, shaping the sweet into floral patterns, spires of translucent art. They tolerated my little acts of nonconformity, my little deviations. After all, my body was the greatest deviation, but the bees recognised that every bodily difference is needed for a specific task: drones for carrying semen, queens for carrying ovum, workers for collecting nectar… they determined that my body and decisions were constructed for a different specialized task and shifted patterns to incorporate this new role.

We homeless lost ones, we refugees of human greed and violence, built ourselves a sanctuary in the woods – a mixture of cathedral and home to remind ourselves that sanctuary is something ethereal, something transcendent and that home can be a collective space. I became a worker in the hive with them, making our home a place of unity.

And yet our lives were not shaped by production as humanity generally projects onto the bees. We celebrated constantly, dancing out our feelings for each other at the same time as our footsteps spoke of new flowers to harvest for nectar, singing songs of a droning buzz to keep our stories alive, and spinning scents of poetry to one another, layers of flavoured breezes to share our ideas and philosophies.

I know I would be accused of animism if I lived in the village still, told that I attributed human feeling and communication to brute insects in order to fend off loneliness… And at least part of me always thought this was true, that my loneliness had driven me mad for companionship, but I could convince at least part of myself – the part that learned to emulate the drone of wings, ventured into the forest to find meadows of new flowers, and who believed her belabored stumbling in circles was part of the dances that bees used to communicate – that I belonged. Besides, with the power to shape honey by my glucomantic will, was anything really outside of the realm of possibility?

So I surrendered to my life of collective work, to shaping the world’s nectar into flavours of sweetness that could tell stories, paint pictures, reveal the sweetness of life. I knew that delving into the sweet meant that I denied the bitter, the sour… that I edited out the taste of loss, of pain, of murder. I knew that the strongest taste in my honey was that of repression, but the more I created out of sweetness, the more I was able to drone out the voices of memory, the pained screams in my head.

So I wandered the woods in search of new flowers and fruits, new tastes to infuse in my nectar, capturing the passing of seasons only through layers of flavour variety that painted our hive, our home.

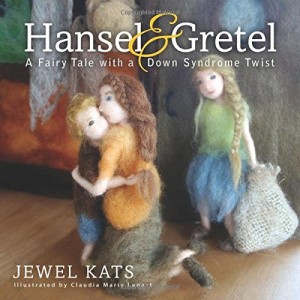

We tend to see children as creatures filled with promise, manifestations of beginnings, but children are like stories and stories always signify an ending at the same time as they point to something new. My ending was titled Hansel and Gretel, two names that signified a change, an interruption, and an erasure as well as a reminder of the human life I had escaped in my attempt to become inhuman.

Hansel and Gretel were stories of remembrance.

***

“Children are meant to be seen and not heard”

“You disgust me – parasite, living off of my womb’s blood, then my milk, and now you steal my youth with your demands for food. Parasite.”

“This is good for you. I don’t take any pleasure in this, but I need to beat the demon out of you. It’s the only way you’ll be a good, worshipful adult.”

Mother’s ranting filled my dreams before the buzzing of my yellow and black children lulled me back into a sense of safe complacency. Their fuzzy bodies nuzzled against my skin, providing me with comfort, driving away memories that stung.

I opened my eyes to sunlight filtered through the honeycombs of my home, rays of yellow filled with dancing, furred shadows suspended impossibly in the air. The light cast patterns across our house, slanting lazy rays of warmth around the room drawing us together. Everything smelled of honey and all of the fecundity it lent to the young – those precious larvae whose bodies moved with constant change and potential. The dizzying scent filled the air, lending me the feeling that I, too, was hovering with transparent wings.

I heard the agitated buzzing before I saw the things that evoked it. The change in their mood seemed to buzz up from my own stomach, turning it into thousands of stingers dripping a venom of anxiety.

The horrifying, distorted shapes filled the yellow light of the honeycomb with darkness, a horrifying spread of pollution across the yellowed light. The gnawing, grinding grunting sound filled me with disgust, but not as much as the buzzing screams of the young, torn by greedy teeth in their lust to eat a home of honey. Greasy fingers tore at the edges of my sugary stained glass, ripping it from bee wax and the incubating warmth for the young. I could see their innocent forms wiggling at the edges of the torn honeycomb, crushed by fingers probing deeper into the honey.

My lips began vibrating with a buzzing that couldn’t be held back by lips pressed in tight rage, air escaping in vibrating surges.

I wouldn’t kill these new destroyers of our home. I would invite them in and make them see the horrors that a home destroyed could bring to bear upon them.

They looked like human children, I suppose I realised later… but in the moment, they were wasps, parasitically invading our home, eating our resources, and planting their horrible, parasitic offspring into our bodies. Eating and eating and eating.

Hansel and Gretel were greedy little wasps and I began to wonder if I could feed them enough honey that they would become a hive for the tiny larvae, those tiny baby bees whose homes they had consumed.

I wouldn’t let them send us back into exile.

Derek Newman-Stille (Story and Art)

is a the Aurora Award-winning creator of Speculating Canada. Derek identifies as queer and disabled. He lives in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, where he researches representations of disability in Canadian Speculative Fiction at Trent University as a PhD student in Canadian Studies. Derek has created art for Lackington’s and Postscripts to Darkness.